The Man with a Cauliflower Ear, Part I: Transcription of the Case Research

- Oct 13, 2018

- 19 min read

Thanks to Dr. John Arthur Horner of Kansas City, Kansas, whose work on researching this one was critical.

This part is but a transcription of his study.

A little before 11 p.m. on Thursday, January 3, 1935, Robert Lane was driving on 13th Street. Lane worked for the Kansas City water department. He later said that as he drove he noticed something rather strange. As he approached Lydia avenue, he saw a man was running west on the north side of the street. This man was clad in trousers, shoes, and an undershirt. That’s all. Though the day had been pretty mild by January standards, he must still have felt chilled.

He waved and shouted to Lane to stop. He approached Lane’s stopped car, but slowed, furrowing his forehead. He apologized, saying, “I’m sorry. I thought you were a taxi,” then looked up and down the street. “Will you take me to where I can get a cab?”

Lane nodded, and replied, “You look as if you’ve been in it bad.”

The man grumbled, “I’ll kill that—” (here the Times printed a long dash to indicate a deleted expletive) “… tomorrow,” as he opened the door and got into the back seat.

Lane glanced at the man, shifted gears, and headed his car toward 12th and Troost. He stared quietly at the man through his rearview mirror, noticing a deep scratch on his left arm. He also noticed that the man cupped his hands. Lane thought that the man might be trying to catch blood from a wound more profound than the scratch on his arm.

As the car approached the desired intersection, the man thanked Lane as he jumped out, then ran to the driver’s side of a parked taxi, opened the door, and honked the horn. Very quickly the cabbie could be seen hurrying from the restaurant where he had been eating.

Lane drove off.

On Wednesday, the second day of the New Year, a lone man, carrying no luggage, entered the Hotel President at 14th and Baltimore, four blocks from the Central Library. He apparently had one of those faces that different people read in different ways. One account gives his age as 20-25, another 25-30, and yet another around 35.

It was about 1:20 in the afternoon.

The man went to the front desk and asked for an interior room several floors up. He signed the register as Roland T. Owen, and gave Los Angeles as his home address. He paid for one day.

Owen had a cauliflower left ear, which made it easy for people to see him as a professional boxer or wrestler. He had dark brown hair and a large, horizontal scar in the side of his scalp, rising above his ear. This was at least partially covered by hair that he had combed over the disfigurement. The desk clerk gave Mr. Owen the key to room 1046 and sent bellboy Randolph Propst with him to the elevator, to show Owen the way to his room. Propst later described Owen as neatly dressed, wearing a black overcoat.

Propst and Owen chatted on the way up to the tenth floor. Owen told the bellboy that he had been at the Muehlebach Hotel the night before, but they had charged him the outrageous price of $5.00 for his room. (With inflation, $5.00 in 1935 had the buying power of a little over $80.00 in 2012 dollars.)

As the two got off the elevator on the tenth floor they turned right and headed down the corridor, turned left at the corner, then left again when the corridor reached the corner with the stairwell. Room 1046 was just down the hallway on their left, on the inner row of rooms looking down on the hotel’s court, rather than the outer row that looked down on 14th Street. Owen unlocked the door and entered while Propst turned on the light.

Owen walked through a short entryway—closet to his right, bathroom to his left—and saw the room itself. Beyond the entryway, it measured nine feet wide and 12 feet long. The bed was to his right and the small stand with the telephone to his left. Situated more or less along the middle of the left wall stood a writing table with chair, and beyond that, angled in the northwest corner, was the dresser. Angled in the northeast corner was an easy chair.

Propst watched as Owen took a black hair brush from his overcoat pocket, along with a black comb and toothpaste. That was it.

Owen placed the three items above the sink, and the two men then exited the room and were headed back down the hallway, toward the elevator, when Propst asked if it was okay with Owen if Propst went back to the room and locked it. Owen gave him the key, and Propst went back to the room, turned off the lights, and locked the door. He then returned to Owen, gave him the key, and the two of them took the elevator back to the first floor, where Propst went back to his duties and Owen left the building.

The maid that first day, Mary Soptic, had come back to work after a day off, and around noon went to room 1046 to clean, finding the door locked. She knocked, and Owen let her in, which surprised her a little, since a woman had been staying in the room before Soptic’s day off. Apologizing, she said she could call back later, but Owen said it was all right, and to go right ahead. Just moments later, Owen told her not to lock the door—that he was expecting a friend in a few minutes. Soptic noticed that the shades were tightly drawn (this was true every time she or any other member of the hotel’s staff entered), and that the lamp on the desk provided the only light, which was rather dim.

In her signed statement to the police, she said that, from his actions and the expression on his face, Owen seemed like “he was either worried about something or afraid,” and that “he always wanted to kinda keep in the dark.”

While Soptic continued cleaning, Owen put on his overcoat, went into the bathroom to brush his hair, and then left the room, reminding her to leave the door unlocked, because “he was expecting a friend in a few minutes.”

Mary Soptic didn’t see Owen again until about four o’clock, when she went back to 1046 with the fresh towels that had finally been delivered by the laundry. The door remained unlocked, the room was dark, and she could see from the light from the hallway that he was lying across the bed, completely dressed. Presumably from the light from the hall, she noticed a note on the desk.

“Don, I will be back in fifteen minutes. Wait.”

The next morning, Thursday, January 3, Soptic headed to 1046 around 10:30 to clean it. Assuming that Owen was out, she unlocked the door with her passkey (which she could only do if it had been locked from the outside) and entered.

Owen was sitting in the dark.

Soptic realized that someone else had locked the door from the outside.

The telephone rang.

Owen answered, and after a moment said, “No, Don, I don’t want to eat. I am not hungry. I just had breakfast.” After a moment he repeated, “No. I am not hungry.”

After cradling the phone, Owen asked the maid about her job. Did she have charge of the entire floor? Was the President a residential hotel? Then he looked around, and said that the Muehlebach Hotel had tried to hold him up on the price for an inside room just like 1046.

Soptic finished cleaning, gathered up the soiled towels, and left.

Around four o’clock that afternoon, after the clean towels had arrived from the laundry, she took a fresh set to Owen’s room. She heard two men talking, and knocked gently on the door.

A rough voice asked, “Who is it?”

The maid identified herself and said that she wanted to leave the clean towels.

“We don’t need any,” replied the rough voice loudly, which was peculiar since Soptic knew there were no towels in the room, having removed them herself that morning.

That afternoon, Jean Owen (no relation to Roland T.), a 30-year-old woman who lived in Lee’s Summit, drove into Kansas City to do some shopping and then meet with her boyfriend, Joe Reinert, who worked at the Midland Flower Shop. After a few hours shopping, she started to feel ill and went to the flower shop and told Mr. Reinert that she didn’t feel up to going out that night, and that she would get a room at the Hotel President so she could avoid driving back to Lee’s Summit till the next day. She told Reinert that she would let him know what room she was staying in. She arrived at the Hotel President about six o’clock and registered a little over half an hour later.

Jean Owen called Reinert about ten to seven and told him that she was staying in room 1048. He came to the hotel about two and a half hours later, and they visited for another two hours, when he left.

In her statement to the police, she said that during the night she

heard a lot of noise which sounded like it (was) on the same floor, and consisted largely of men and women talking loudly and cursing. When the noise continued I was about to call the desk clerk but decided not to.

Charles Blocher was the elevator operator for the graveyard shift at the hotel, and he started work a little before midnight on January 3. For the first hour and a half of his shift he was pretty busy, but around half past one business tapered off, though there seemed to be a fairly boisterous party in room 1055. As he puts it in his statement, sometime in the first three hours:

"[I] took a woman that I recognized as being a woman who frequents the hotel with different men in different rooms. It is my impression from this woman’s actions that she is a commercial woman. I took her to the 10th floor and she made inquiries for room 1026 (sic) – about 5 minutes after this I received a signal to come back to the 10th floor. Upon arriving there I met this same woman and she wondered why he wasn’t in his room because he had called her and had always been very prompt in his appointments and she wondered if the might be in 1024 because the light was on in there the transom was opened – she remained about 30 or 40 minutes then I received a signal to go back to the 10th floor – I went back and this same woman appeared there and came down on the elevator with me and left the elevator at the lobby. About an hour later she returned in company with a man and I took them to the 9th floor – I later received a signal to go to the 9th floor at about 4:15 AM and this same woman came down from the 9th floor and left the hotel. In a period of about 15 minutes later this man came down the elevator from the 9th floor complaining that he couldn’t sleep and was going out for a while."

The woman’s searching for 1026 rather than 1046 raises some interesting questions. Was she actually there to see Owen, or was it another man altogether? Did she get the room number wrong, or did Owen inadvertently give her the wrong number? Did this woman have anything to do with what happened in 1046 that night? (The use of 1026 as Owen’s room number appears to have gone out over the wire service account of the story, as that is what appears in the accounts I have seen in papers from the south and the northeast parts of the country.)

Blocher described the man as being about five foot six, slender, about 135 pounds, wearing a light brown overcoat, brown hat, and brown shoes. The woman was about five foot six, with black hair, weighing about 135 pounds, wearing a “coat of black hudson seal or imitation hudson seal.” The coat had a collar with a light fur strip, and the collar stood up.

The woman was also noted by James Hadden, hotel’s night clerk, when she left the building. He recognized her as someone he had seen “in and out of the hotel at various times and at various hours of the night and early mornings.”

The next known encounter between Owen and the hotel staff took place Friday, just a little after seven o’clock, when Della Ferguson, the telephone operator, took over the board. She noticed that the board indicated that the phone for 1046 was off the hook. At ten after, when the phone was still off the hook, with no one using it, she requested that bell service send a bellboy up to the room to tell the occupant to hang up the phone.

The bellboy was Randolph Propst, who had taken Owen up to the room when he had first checked in. When he got to Room 1046 the door was locked, and a “Don’t Disturb” sign was hanging from the knob. Propst knocked loudly and got no response. After a moment he again knocked loudly and finally heard a deep voice say, “Come in.” He tried the doorknob and, yes, it was locked. Again he knocked, and this time heard the deep voice tell him to “Turn on the lights.” He knocked yet again, and again, and finally, after seven or eight times, yelled through the door, “Put the phone back on the hook!” He got no response and returned to the lobby, where he told Della Ferguson that the guy in the room was probably drunk, and that she should wait about an hour and send somebody else up them.

About half past eight, Della Ferguson noted that the phone for 1046 was still off the hook, and she sent bellboy Harold Pike up to ask Owen to replace the receiver. When Pike got there, he found that the door was still locked, and he used a passkey to let himself in—again indicating that the door had been locked from the outside. With the light from the hallway, Pike noted that Owen was lying on the bed naked, surrounded by what appeared to be dark shadows in the bedclothes, apparently drunk. He also saw that the telephone stand had been knocked over, and that the phone was on the floor. Pike straightened the stand and put the phone on it, securing the receiver in its place.

He locked the door behind him and returned to the lobby, telling his supervisor that Owen was lying naked on the bed, apparently drunk.

Around 10:30 to 10:45 that morning another operator reported to Betty Cole, the head operator, that the phone for 1046 was again off the hook. Around 11 o’clock Randolph Propst headed back up to the room, noting that the “Don’t Disturb” sign was still on the door. After knocking loudly three times with no response, he unlocked the door with his passkey and entered.

"[W]hen I entered the room this man was within two feet of the door on his knees and elbows – holding his head in his hands – I noticed blood on his head – I then turned the light on – placed the telephone receiver on the hook – I looked around and saw blood on the walls on the bed and in the bath room – this frightened me and I immediately left the room and went downstairs"

Propst rushed to the assistant manager, M.S. Weaver, and told him what he had found. Joined by Percy Tyrrell, they hurried back to 1046, but could only open the door about six inches—apparently Owen had collapsed on the other side of the door.

Newspaper accounts, however, conflate the action, having Propst discovering Owen sitting on the edge of the bathtub, his head resting on the top of the sink, which occurred a short while later.

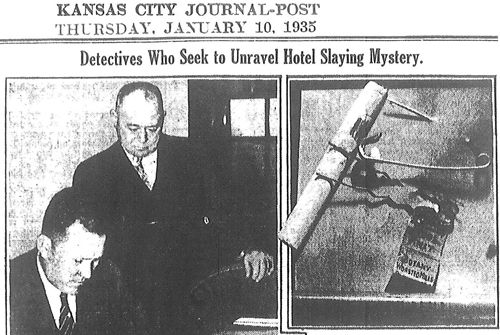

The police arrived in short order—Detectives Ira Johnson and William Eldredge, and Detective Sgt. Frank Howland—and at some point in this time Dr. Harold F. Flanders arrived from General Hospital. They were later joined by Detective D.C. King.

Owen had been restrained with cord—around his neck, his wrists, and his ankles—and looked like he had been tortured. Knife wounds bled on his chest from over his heart. One of these had punctured his lung. His skull was fractured on the right side, where he had been struck more than once. There was bruising around the neck, suggesting strangling as part of the torture. Besides the blood that was on the bed itself, more blood had spattered onto the wall next to the bed, and a small amount of blood could even be seen on the ceiling above the bed.

When Dr. Flanders arrived, he cut the cords around Owen’s wrists. His hands freed, Owen turned on the bathtub spigot, which Flanders shut off. Detective Johnson asked Owen who had been in the room with him. Owen, semiconscious and barely able to talk, said, “Nobody.” How had he gotten hurt? “I fell against the bathtub.” Had he tried to commit suicide? “No,” he mumbled, and then started to slip fully into unconsciousness.

Owen was rushed to the hospital.

Dr. Flanders later put the inflicting of the wounds at six to seven hours earlier, since a lot of the blood on the body had “dried to a hard mass,” and the blood on the walls and furniture had “solidified.” This would place the stabbing and cutting at well before Propst’s 7:00 trip to 1046.

As the detectives searched Room 1046 they began to realize that what they did find might not be as telling as what they didn’t. There were no clothes in the room, anywhere—no black overcoat, no shirt, no undershirt, no pants, no shoes or socks. The closest thing to clothing was the label from a necktie. Also missing were things like the usual hotel-supplied soap, shampoo, and towels. And any sort of knife or other weapon that might have been used in the stabbing and cutting.

This last, along with the cords that had bound Owen, early caused the police to set aside the possibility of suicide.

Beside the label (which showed the tie as originating from the Botany Worsted Mills Company, of Passaic, New Jersey), the only items found were a hairpin, a safety pin, an unlighted cigarette—and a small, unused bottle of dilute sulfuric acid.

There were also two water glasses. One remained on the shelf above the sink, and the other lay in the sink, missing a jagged piece. The glass top of the telephone stand yielded four small fingerprints, possibly from a woman.

The Kansas City Star and the Kansas City Journal-Post, the city’s evening papers, both carried the story on page one that day. The Journal-Post quoted Detective Johnson as saying that “There is no doubt that someone else is mixed up in this.”

Jean Owen was held for questioning, and was finally released when police were able to verify her account with Joe Reinert.

Roland Owen slipped into a coma before they got him to the hospital. He died a little after midnight that night, Saturday, January 5.

During the night the police queried the Los Angeles police, who found no record of any Roland T. Owen. Before the night was over, via the wire photo process, the photo lab at the Star sent Owen’s fingerprints to the Justice Department’s Bureau of Investigation (the future FBI).

Doubts were already being raised as to whether Roland T. Owen was the actual name of the victim. A woman had called the Hotel President during the night to ask for a description, and said the victim was a man who lived in Clinton, Missouri. By Sunday the Journal-Post reported that “Police believe Owen registered under an assumed name.”

This was just the start.

On Sunday people viewed the body at the Mellody-McGilley funeral home. One report says 50—another says over 300. One of the viewers was Robert Lane.

Lane identified the victim as the man who had stopped him on 13th Street. He saw the deep scratch on the arm that he had noted Thursday night. He was sure that this was the man who had waved him down under such unusual conditions.

Detective Johnson, though, dismissed the identification, not believing that the passenger was “Owen,” though I haven’t found anything that indicates he doubted that Lane picked up somebody.

Police said they did not see how “Owen” could have gotten out of the hotel without any of the staff or passersby noticing him. (This, of course, presupposes that “Owen” was dressed the way Lane describes when he left the hotel.) Another account says “enter” the hotel.

The story had been picked up on the wire services, and more and more people started contacting the Kansas City police to see if the victim might be the relative or loved one who had gone missing.

Most of these either included no description or picture of the missing relative, or they sent a description or picture that bore no resemblance to “Owen.” The police began requesting that people send pictures to help speed the identification. The KCPD also started sending letters and telegrams to police departments in cities throughout the country, trying to track down the large number of leads they were amassing.

The police established that “Owen” had been “seen in certain liquor places on 12th street in the company of two women.”

As the detectives started to hear back from other police departments around the country, they began to close out the huge number of leads they had received. The rate of new leads slowed.

Upon re-examining the room on Sunday, police briefly thought they had come upon an important clue when they found a discarded towel that was covered with blood. They concluded, though, that the towel had been left by a hotel employee who had been sent to clean after the initial forensic examination by the police. I assume that someone remembered Soptic’s statement that she had picked up the soiled towels on Friday morning and had not been allowed to deliver the fresh ones that afternoon.

At some point the detectives followed up on the statement that “Owen” had stayed at the Hotel Muehlebach the night before he came to the President. They found that no one named Roland T. Owen had registered at the Muehlebach. But on the night in question, a man who looked like the picture had stayed there, insisting on an interior room—and he had given Los Angeles as his home address.

His name in the register was Eugene K. Scott.

The police contacted the LAPD again, this time concerning Eugene K. Scott, and received the same response as they had gotten for their query about Owen.

The Los Angeles police found no record of anyone living in Los Angeles named Eugene K. Scott.

The detectives tried to find out more information about the other man, the one who was coming to be known as “the mysterious ‘Don.’”

Was he the same man who was in Owen/Scott’s room with the unnamed woman Thursday night and Friday morning? Were they the couple who both stood about five foot six—he all in brown, she all in black except for a light fur collar on her sealskin coat? Could he be the rough voiced man who told Mary Soptic through the locked door that room 1046 didn’t need any towels when she knocked on the door Thursday afternoon? Was “Don” the man that the man Robert Lane identified as Owen told Lane (Lane told police) he was going to kill?

We know that Owen/Scott told Soptic that he was expecting a visitor, and to leave the door unlocked when she finished cleaning the room. She later heard him talking with “Don” on the phone.

The search for “Don” continued.

Others came forward and identified the body. Ernest Johnson of Kansas City viewed the body and positively indentified Owen/Scott as his cousin, Harvey Johnson, formerly of Dallas. Ernest Johnson’s sister, Mrs. Anderson, came to view the body later, and told police that her cousin Harvey had died five years ago. Ernest was surprised and indicated that Owen/Scott looked exactly like Harvey.

On Friday night, January 12, Toni Bernardi of Little Rock, Arkansas, viewed the body at Mellody-McGilley. Bernardi was a wrestling promoter, and he identified Owen/Scott as the same man who had approached him several weeks earlier, wanting to sign for some wrestling matches. Bernardi said the man had given his name as Cecil Werner, and had said he had wrestled for Charles Loch of Omaha.

On Saturday, Loch looked at pictures that had been sent to Omaha, but did not recognize Owen/Scott as anyone who had ever wrestled for him.

On Tuesday, January 15, Lester W. Kircher and Clarence T. Ratliff, two city detectives were reassigned to the homicide squad. The squad was investigating two other murders beyond the one at the Hotel President.

On Monday morning Vincent J. Cibulski, manager of the Mid-State Finance Company, was in his back yard when he was shot in the abdomen and shoulder after getting out of his car. Monday night carpenter John Logan was found near Missouri Ave. and Harrison St. in an alley. Logan appeared to have been killed with an ax.

As time went by, the detectives continued to follow up leads, but the Owen/Scott case seemed to grow colder and colder. On Sunday, March 3, the Journal-Post published an announcement that Owen/Scott would be buried the next day in the potter’s field. Detective Johnson said he still hoped someday to identify the man who had been so mysteriously murdered.

The burial did not take place as announced.

Mellody-McGilley received an anonymous phone call. The caller asked that the body not be buried immediately, and promised that he or she would soon send funds to cover the costs of a funeral. On Saturday, March 23, Mellody-McGilley received a special delivery envelope containing cash wrapped in a newspaper. It was enough to pay for the funeral and burial. The sender remained unidentified.

The funeral home shared the information with the police, and the funeral was held and Owen/Scott’s body was buried in Memorial Park Cemetery in Kansas City, Kansas. On Wednesday, a woman called the Journal-Post, refusing to identify herself, and told the paper that “Roland Owen was not buried in the potter’s field. Call the undertakers and the florists and you’ll learn that Mr. Owen’s funeral expenses were paid and that a floral tribute was placed on his grave.”

The flowers were secured from the Rock Flower Company, in much the same way as the funeral and burial were set up, although the anonymous money to cover the bouquet of 13 roses had to be sent twice. With the $5 payment for the flowers was a card to be placed with the flowers on the grave. It read, “Love for ever—Louise.”

The Rev. E.B. Shively of Roanoke Christian Church conducted the funeral, and the only people who attended were police detectives.

The police continued to try and track down the elusive “Don,” looking into different possibilities, but with no conclusive success.

In mid May, The American Weekly magazine, a Sunday supplement published by the Hearst Corporation, carried a sensationalistic account of the murder titled “The Mystery of Room No. 1046.” This contained a photograph of Owen/Scott’s profile, presumably taken as he lay on the coroner’s table.

(In the police file on the case I have also found a letter from Harry Keller, editor of Official Detective Stories to Chief of Detectives Thomas Higgins, KCPD, indicating that his magazine later had also published a review of the case.)

And that’s where things stood, with little real progress towards finding out Owen/Scott’s real identity or finding his killer.

Nothing obvious happened for another year and a half.

In the fall of 1936, another woman thought she recognized Owen/Scott’s picture when she came across the American Weekly article, or the Official Detective Stories review. The picture looked very much like the son of a friend of hers, whom the family had not seen since he left Birmingham, Alabama, in April of 1934.

For over a year Ruby Ogletree had not received anything from her son, except three short, typed letters, the first of which was mailed in the spring of 1935—after Owen/Scott had died. Mrs. Ogletree had exchanged more than one letter with J. Edgar Hoover, and she had written to the U.S. consul in Cairo, Egypt, seeking help in finding her son.

When she received the magazine from her friend, she finally verified what she had long feared—her son was dead.

Mrs. Ogletree exchanged letters with the KCPD, and on November 2, 1936, twenty months to the day that he had registered at the Hotel President, several newspapers around the country carried the story that let us know that Roland T. Owen’s real name was Artemus Ogletree. His mother gave Ogletree’s age as 17. She also explained that the scar in the scalp above his ear was the result of a childhood accident when he was burned by some hot grease.

Over time other facts came out. One of the most important of these was that, during his time in Kansas City, Ogletree had stayed at a third hotel, the St. Regis, sharing a room with another man, who may have been the mysterious “Don.”

But the main questions remained unanswered. Who killed him? Why was he killed? What exactly happened in room 1046 that night? Was “Don” the rough voiced man? Who was Louise? Was she the woman whose voice was heard?

The case remains unsolved. There are reports that are dated into the 1950s in the case file that usually end with the detective writing something along the lines of “I will continue to pursue the investigation.”

And that’s where things stand today.

Except …

Dr. John Arthur Horner of Kansas City, Kansas, received a quite strange phonecall which he describes in his case research.

"[A]bout eight or nine years ago, when the Main Branch of the Library filled the northern half of the Board of Education Building on 12th St., and the Missouri Valley Room was located on the third floor, I took an out of state phone call from someone who asked about the case.

This person and another had been helping itemize the belongings of an elderly person who had recently died. They found a box with several newspaper clippings about the case. The caller said that, besides the newspaper clippings, something mentioned in the newspaper stories was also in the box.

The caller tantalizingly refrained from telling me what that something was."

Comments